The first step in beginning any enterprise is identifying an opportunity. Therefore it is important to identify the categories of opportunity that utility bicycles present. I see two categories: the first being load carrying, the second being mobile services. As a load carrier, a bicycle is often the right combination of purchase cost, carrying capacity, upkeep expense, size, agility, and speed for the task at hand. The opportunity in the second category is the bike's ability to add value to traditional services by making those services mobile (think ice cream carts, paperboys, and mini-mart corner stores). In places where cheap and easy transport is less taken for granted as it is in wealthy parts of the U.S., services that come to you instead of you going them have increased value. Here in Nairobi for example there are traveling knife sharpeners, veg etable vendors every 10 meters, butchers, furniture makers, and cyber cafes on every corner. In an environment like this “going” shopping almost becomes obsolete.

etable vendors every 10 meters, butchers, furniture makers, and cyber cafes on every corner. In an environment like this “going” shopping almost becomes obsolete.

One of the bicycles designed by our predecessor Practical Action working in Kibera with Soweto Youth Group two years ago was a mobile food kiosk (pictured). Outfitted with a stove, t his bike could, for example, deliver hot food to multiple construction sites during the time sensitive window of the lunch hour whereas someone on foot would have a more limited market (this is the same principle employed by the mobile milkman of old). The “Worldbike” I've designed also brings portability to services that require power. I've imagined a portable knife sharpener, battery charger, food sheller, food grinder (like peanuts), a lathe and/or drill dress that can travel to the work site, a blender (a la www.bikeblender.com), a juicer, a sewing machine, a washing machine, (apply your creativity here).

his bike could, for example, deliver hot food to multiple construction sites during the time sensitive window of the lunch hour whereas someone on foot would have a more limited market (this is the same principle employed by the mobile milkman of old). The “Worldbike” I've designed also brings portability to services that require power. I've imagined a portable knife sharpener, battery charger, food sheller, food grinder (like peanuts), a lathe and/or drill dress that can travel to the work site, a blender (a la www.bikeblender.com), a juicer, a sewing machine, a washing machine, (apply your creativity here).

One of the things revealed in surveys that were conducted amongst purchasers of the Worldbike Bigga Boda in Kisumu, is that the bikes tended not to be employed in a single specialized service. For example they might have been used in the morning to deliver bread, in the afternoon to carry passengers, and in the evening to pick up the kids from school and run errands for the family. As a result I concluded that a bicycle with a diversity of applications will produce the most value. My Worldbike design is intended to fulfill that most common employment of a bicycle which is transport while at very little extra cost making the bicycle also upgradeable to a capable power source. In this way I imagine the bicycle creating value for its owner all day long. Again, start the discussion here:

http://flickr.com/photos/27342523@N06/sets/72157606002071374/

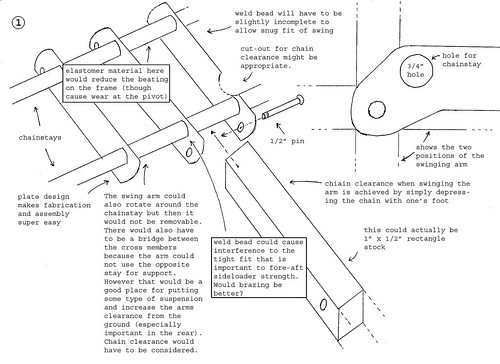

SideLoaders: Talking with members of the youth group about their trash collection business I learned an important lesson. Currently the group hauls mixed was

te to their collection site and then sorts it for compostable material, recyclables, and landfill-bound waste. When I asked why they give themselves that messy sorting job versus asking the households to sort the material, it was explained that house space is too valuable to take up with multiple trash buckets. When asked about leaving the buckets outside, I was told they would get stolen. This helped drive home the fact that a bicycle used by a poor person needs to be stowable which means that it needs to fold into a small

package. Bikes that are also narrow (hence the attraction of the two-wheeled design) fit better through crowded streets and tight neighborhoods. I'm far from the first person to be attracted to the folding design as can be seen from the following old photos showing Worldbike founder Ross Evans in South Africa with a side-loading bike. My design however seeks to eliminate the interference caused by the chains that support the platform.

package. Bikes that are also narrow (hence the attraction of the two-wheeled design) fit better through crowded streets and tight neighborhoods. I'm far from the first person to be attracted to the folding design as can be seen from the following old photos showing Worldbike founder Ross Evans in South Africa with a side-loading bike. My design however seeks to eliminate the interference caused by the chains that support the platform.

Kickstand: A solid centerstand kickstand is a must for any cargo bike as a stable platform is needed for loading and unloading and simply for keeping a laden bike upright. Here I took inspiration from the black mamba kickstand design. On my bike, the kickstand is also critical for lifting the rear wheel when using the bike as a power source.

Implement Rack: The top rack is a standard platform for load carrying but can dually be used for implement mounting and as a stable bench top. The following pictures show how to attach a pulley to the spokes with two pieces of tire and plate steel thus converting any wheel into a drivewheel/flywheel.

Secondary Seat Tube: In order to use the bike as a power source, the rider needs to be able to turn around and access the rear of the bike while pedaling. Simply moving the seatpost to an alternative position allows for this. Correspondingly, moving the handlebars or another t-shaped bar to the seat tube provides the needed hand support.

The one problem with building one-off load-hauling bikes like this in Kenya is the availability of strong wheels and forks. A connection I made last week to an Indian importer might provide a source for small quantities but the general rule of thumb is that if you want parts from India or China the minimum quantities start at 100,000 units. Realistically, if a bike like this is to make a real impact then it needs to be mass produced in China where all the specs can be met, materials are cheap, and productivity is high.

.jpg)